Scott Frost, a former football coach at Nebraska, filed a lawsuit on Friday against the University of Nebraska and its Board of Regents regarding the handling of his buyout payments following his termination in 2022, taking his long-running contract dispute with his former employer to court. The contentious relationship between college coaching contracts and compensation in contemporary college football is highlighted by the legal battle, which has its roots in millions of dollars, tax issues, and contradictory contract language.

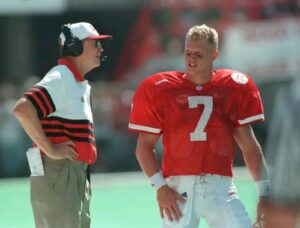

After a disappointing run that left him with a 16–31 record at his alma mater, Frost, who played quarterback at Nebraska before returning as head coach, was fired by the Cornhuskers on September 11, 2022, just three games into the season. His contract was set to expire on December 31, 2026, and it contained a sizable buyout clause worth about $15 million, which is essentially the remaining amount of his guaranteed compensation following termination.

Frost claims that the university violated its contractual duties and improperly managed the timing and reporting of his buyout payments in his lawsuit, which was submitted to the Lancaster County District Court in Nebraska. How the school reported those payments for tax purposes and whether it improperly withheld amounts he feels he still owes are at the heart of the dispute.

Tax Liability on Money He Never Received

Nebraska told Frost in December 2022 that it planned to include the present value of his 2025 and 2026 liquidated damages payments basically, projected future buyout money on his 2022 W-2 tax form, according to the court filing. Frost’s attorneys claim that this was an improper and incorrect move. According to the filing, Nebraska created a tax liability of about $1.7 million on money that Frost had not yet received and might not receive at all under the contested contract interpretation by including that projected value as taxable income for 2022.

Frost did not receive the W-2 until September 2023, well after the deadline that would have enabled him to file his 2022 tax return on time, according to the lawsuit. Frost asserts that this delay increased the financial impact of the initial reporting decision by exposing him to late filing penalties, legal fees, and an IRS audit.

Conflicting Contract Interpretations

Frost’s main complaint is that the payments he owes for 2025 and 2026 should not have been subject to reduction, offset, or forfeiture because they were guaranteed by the original agreement. However, according to Frost’s lawsuit, the university’s own correspondence contradicts that claim. Although Nebraska stated that it intended to include the anticipated future payments on the W-2, it also included language implying that those same payments could be changed later “without any further explanation.” That contradiction, according to Frost’s lawyers, is “muddled, internally inconsistent, and transparently self-serving.”

The so-called “offset” clause in Frost’s contract is another significant source of disagreement. This clause, like many coaching contracts, permits the university to lower the amount owed in the event that the coach finds another job. According to the lawsuit, Nebraska would have to pay Frost in full for 2025 and 2026 since the clause expired on December 31, 2024, which is when Frost claims his original contract would have naturally ended. According to Frost’s filing, the school still owes him about $2.5 million annually for those final two seasons because the offset period ended before he started his current position.

Nebraska, however, argues that the offset is still in place until the initial contract expiration date of 2026. The Cornhuskers contend they owe Frost nothing under that interpretation since he was appointed head coach at the University of Central Florida (UCF), where he receives an annual salary of almost $4 million. The question of whose interpretation of the contract will stand up to judicial scrutiny is now at the heart of the legal dispute.

Seeking Damages and Clarity

Frost is requesting that the court issue a declaratory judgment outlining the rights and obligations under the contract in addition to awarding him at least $5 million in damages, which is a portion of the sum he feels he is owed. A legal determination of how and when Nebraska’s offset clause expired, as well as whether the university’s actions were acceptable under the terms of the agreement, is a crucial part of that request.

Apart from the monetary consequences, the lawsuit depicts a coach who feels his former employer behaved irrationally and improperly, resulting in an unforeseen tax burden, delayed paperwork, and uncertainty in his career. According to Frost’s filing, Nebraska was “uncooperative, dismissive and refused to acknowledge or correct” the harm it caused, making his attempts at constructive communication with the university fruitless.

What Happens Next?

Nebraska has not yet publicly addressed the lawsuit’s allegations, and no court date has been set. Contract interpretation, tax law, and the precise wording of the buyout terms may ultimately determine the outcome of the case. For Frost, who is currently coaching again and hoping to succeed at UCF after his time at Nebraska, the lawsuit is about more than just money. It’s a conflict between the unpredictable realities of college athletics and large coaching contracts, as well as issues of fairness and interpretation. The result might have wider ramifications, possibly affecting how reporting requirements and buyout clauses are managed in collegiate athletics.